A reflective blog authored by Dr. Rintaro Mori, UNFPA Asia and the Pacific’s Regional Advisor on Population Ageing and Sustainable Development, on the occasion of International Day of Older Persons.

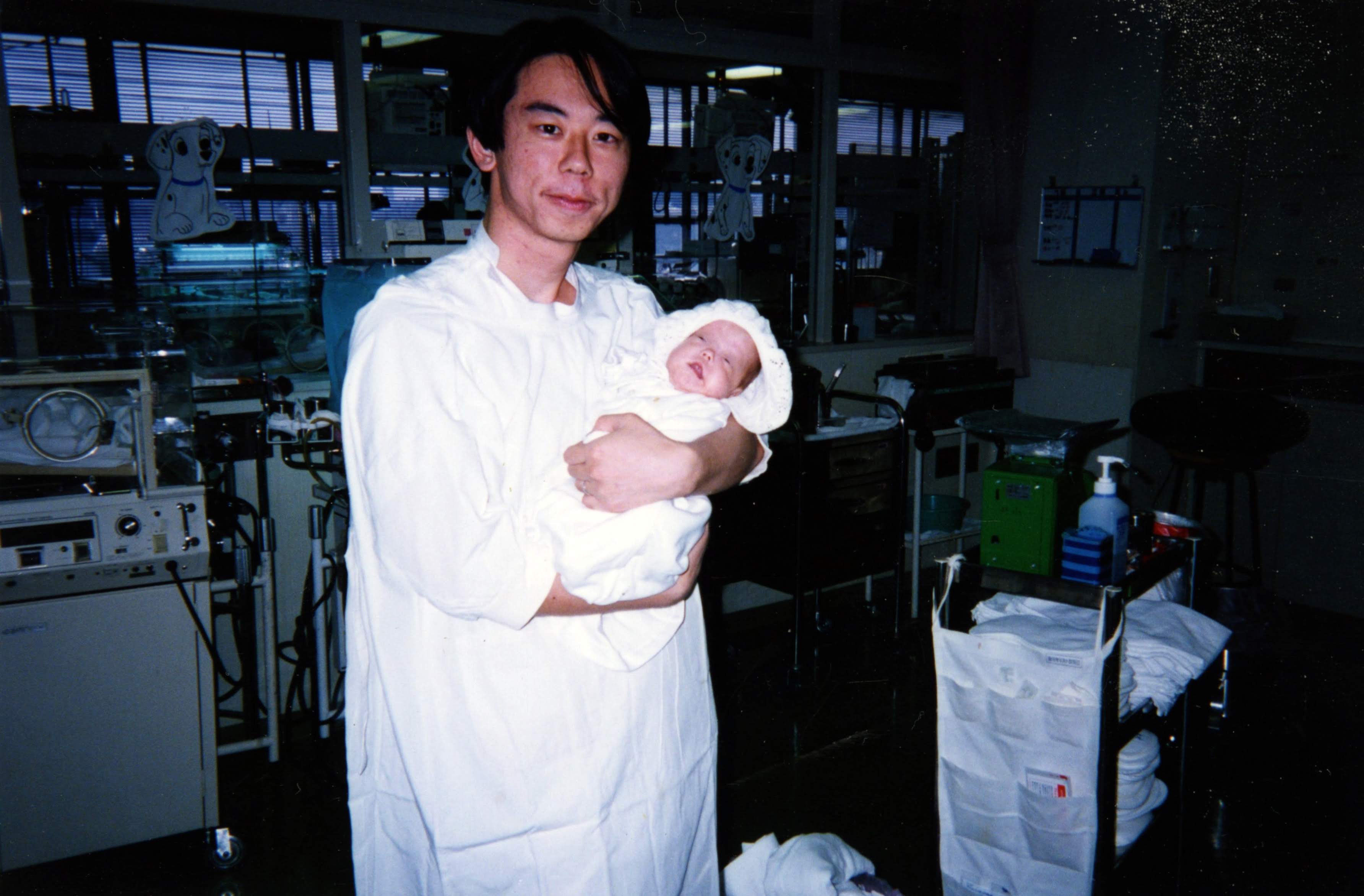

Towards the end of my foundational neonatal clinical training in Japan, I was researching the bone density of babies who were born smaller than the average size and/or prematurely after their prolonged stay in intensive care. This groundbreaking research, the first of its kind at the time, revealed that despite reaching physical growth milestones similar to babies of the same age, these infants lacked a substantial portion of bone density.

These findings not only earned me a PhD but, more importantly, unveiled a pivotal aspect of childbirth: mothers contribute a significant amount of bone content to their fetus towards the end of their pregnancies.

Both mothers and infants experience a deficiency in bone density if they are not properly managed clinically, and it takes several years for them to catch up with their peers. Furthermore, this issue can resurface in the later stages of their lives.

Later in my academic career, spurred by these findings, I led a team in conducting systematic reviews on these matters. The results were startling, showing that nutritional and biological conditions before and after childbirth result in significantly elevated risks of developing conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, mental illnesses, and even cancer in these infants during their later years.This hypothesis is known as the Developmental Origin of Health and Disease (DOHaD). A notable example is the women and babies conceived during the Dutch Famine in the Second World War. Babies conceived in the Netherlands during this two-year famine period were more likely to develop hypertension than those conceived before or after the crisis. It was a truly eye-opening revelation.

After completion of my training, I worked as a neonatal pediatrician in an isolated local community. I worked tirelessly, adhering to the traditional Japanese work ethic, living in the hospital, working around the clock, seven days a week, with only two days off in a year.

One fateful midnight, I received a severely injured child brought into our Accident and Emergency Unit, ultimately succumbing to injuries despite hours of intensive treatment. I knew this child. This child was one of the premature babies for whom I had provided weeks of intensive care after birth. Heartbreakingly, I learned that the child had been subjected to physical abuse by the mother, leading to the tragic outcome. The shock was indescribable.

Blame was not an option. The mother had been separated from her child during the critical period for nurturing the mother-child bond. She couldn't connect with the child as her own.

I found myself repeatedly asking one question: How could I have done better? Could I have let the mother spend more time with her baby when she was in intensive care?

I became a national advocate for rethinking the concept of neonatal intensive care, including the implementation of Kangaroo Care in modern clinical settings. Kangaroo Care is a method of a parent or caregiver holding and nurturing a newborn, skin-to-skin, providing warmth, comfort, and bonding. Now, several neonatal units in Japan offer private rooms where mothers and sick infants receive care together in a more intimate environment.

Undoubtedly, numerous scientific studies emphasize the critical importance of the early stages of newborns' lives for their emotional and mental well-being, and how these early experiences shape their lives well into adulthood.

All too often, we, as professionals, exhibit shortsightedness. In my current role as the Regional Advisor for Population and Development at UNFPA Asia and the Pacific, I support countries in developing rights-based population policies. I have observed that when societies are faced with the challenges of ageing, the immediate focus turns to how the elderly can be supported, even though they may not yet perceive themselves as old. Not all older individuals are vulnerable.

The issue is not merely in ageing itself; rather, it lies in inadequate healthcare, insufficient financial resources, a lack of personal freedom, and a loss of respect in society for the older persons.

The renowned Harvard Study of Adult Development illustrates that it is not the amount of wealth accumulated or the level of social recognition achieved that matters most, but the quality of one's relationships with their closest companions. These relationships profoundly impact mental and physical health in later life.

For anyone, the period from conception to early childhood is pivotal for establishing the habits and emotional foundation that will serve as the backbone for their entire life. For a woman in particular, safe pregnancy and childbirth are critical factors influencing her well-being throughout her life course. Without a solid education, proper skills and vocational training, adequate nutrition, and emotional stability during her younger years, it becomes exceedingly challenging to secure a decent job and establish meaningful relationships. When these aspects are met, it leads to financial and emotional stability, fostering a flourishing sense of well-being in her later life. UNFPA advocates for adopting this ‘life-cycle’ approach in realizing girls’ and women’s rights, so that her life is one of fulfillment and empowerment.

On International Day of Older Persons, let’s make sure that we invest in every stage of a woman’s life, especially the early stages, as it lays the foundation for her to age with dignity, emotional resilience, and overall well-being throughout her journey into adulthood and beyond.

–