JAKARTA, Indonesia - Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) has been practiced and preserved for generations in some Indonesian communities. While many in the younger generations may tend to neglect or abandon the practice, those who support it want to preserve the harmful practice as part of what they see as cultural, religious and social norms and traditions.

“I was about 7 years old when my mother organized an FGM/C ritual for me. The paradji (traditional birth attendant) used a piece of sharpened bamboo stick. I was screaming in severe pain and I saw blood coming out. I was and still am very traumatized,” says Helwana, a religious leader from the Indonesian Mosque Council (DMI).

“I remembered my father, who was an ulama (Islamic scholar), was actually against FGM/C, which was a family tradition from my mother’s side. She and her extended family insisted on having me circumcised. After the incident and knowing the pain I had to go through, none of my sisters were circumcised,” explains Helwana, herself an ulama now who has been actively encouraging communities to abandon the practice.

Fallacies and contradictions abound

FGM/C stems from the groundless belief that it purifies girls, helps them control sexual urges, and prevents them from growing up as promiscuous women, among others. Because it is commonly practiced in Indonesia - with one study estimating that 50 percent of all girls undergo it - the Ministry of Health (MoH) initially issued a regulation providing a basis for the medicalization of female circumcision to ensure it was carried out by trained doctors and midwives, to minimize harm to the girls undergoing it. This regulation was later revoked and replaced by another regulation describing the FGM/C practice as having no medical basis or health benefits, and giving a mandate to the MoH and the Syara’k Consultative Board to issue guidelines for the procedure that guarantee women’s health and safety, stipulating that the procedure should not harm or mutilate female genitalia.

MoH also stressed that FGM/C is a violation of women’s reproductive rights and a form of violence against women and girls. The Ministry has conducted some activities to further discourage the practice, including through development of information, education and communication (IEC) materials to raise awareness, highlighting FGM/C at the Indonesian Midwives Association (IBI) National Summit 2018, and incorporating the information into a widely-used maternal and child health guideline.

UNFPA’s joint initiative with UNICEF, the Better Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights for All in Indonesia (BERANI) project funded by Global Affairs Canada, has supported the MoH in the dissemination of the IEC materials. The Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection (MOWECP) has also developed advocacy strategies that target religious leaders, youth and civil society organizations (CSOs), using a family-based approach with support from the BERANI project.

“FGM/C is harmful, and women and girls have the right to be free from torture,” says Risya Kori, UNFPA Indonesia’s Gender Specialist.

Suci Maysaroh, a young midwife, has always known FGM/C has no health benefits. As a fresh graduate working at a private midwifery clinic, she was told to offer FGM/C services as part of a post-natal package along with ear-piercing for IDR 100,000 (~ CAD 9 or USD 7).

“Many believed that it’s a cultural tradition to preserve. So I pretended to perform FGM/C by placing a piece of cloth on the newborn’s genitalia and then pressing it gently with my hand. I knowingly lied to my clients and my supervisor,” she recalls.

“I felt guilty for lying but I thought if I refused to perform the mock FGM/C, parents would likely go to other midwives or worse, to paradji for FGM/C. The latter can use any tool, from razor, scissors, needle, to sharpened bamboo stick, and the methods can vary from rubbing with turmeric, pinching, pricking to cutting,” Suci adds.

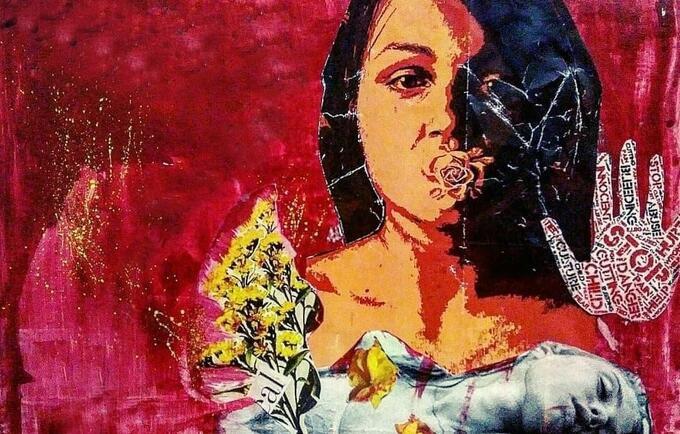

Midwife Suci Maesaroh campaigns against FGM/C, advising parents and communities to abandon the harmful practice. Image: UNFPA Indonesia.

Separately, an ulama from the Indonesian Ulamas Council (MUI) Arif Fahruddin explains that FGM/C is described by some of its proponents as makrumah (honorable deed). It is not a sunnah (habitual practice) but mubah (netral or merely permitted). “However, if the practice is harmful and bringing suffering or muda’rat, it is haram (forbidden) in Islam,” he explains.

The MUI, he adds, issued a fatwa (religious edict) forbidding the banning of FGM/C. “The MUI is of the opinion that the harmful types of FGM/C are haram, while the (non-harmful) symbolic types, like rubbing with turmeric, when done as part of syiar (Islamic teaching) should not be banned,” he insists.

Arif, an advocate for ending FGM/C, says that FGM/C is a cherished tradition mainly among older generation, senior midwives, paradji, and small conservative groups. “The most popular type of FGM/C in communities is rubbing with turmeric. But we have to admit that fundamental groups exist. They are small in number but still practicing and promoting harmful FGM/C.”

Health education for young people

The encouraging news is that the practice is currently no longer popular among the younger generation. Years of campaigns against FGM/C and education may have been fruitful. Younger couples and young people in general are more educated and have better health awareness.

Many midwifery students at Islamic boarding schools (pesantren) say they have not received requests for female circumcision from parents in nearby communities in recent years.

Kyai Ali Muhsin from Darul Ulum Peterongan pesantren says, “I know some ulamas whose daughters are not circumcised.”

He says that seminars on FGM/C, like the one UNFPA recently organized with MOWECP involving ulamas, medical practitioners, and human rights and gender activists as speakers, are very informative and have helped him and other participating ulamas change their views about FGM/C.

“Similar seminars should be organized at the grassroots community level across Indonesia.” The ulama and the pesantren communities have also actively used prayer and community gatherings to raise awareness.

“Mindset and behaviour change take time. We need to educate youth as future parents to reject harmful practices. Ideally, religious leaders and health workers can work together to raise community awareness,” says Arif, who also participated in the UNFPA-organized seminar.

“What we can promote is vulva hygiene for newborn: care and cleaning baby’s genitalia after birth. I persuade parents by giving health explanations to abandon FGM/C because the clitoris has many nerves and the baby would be in pain if it was rubbed or pierced. Based on my experience, they (parents) would change their mind because they don’t want to hurt their babies,” Suci, the midwife who campaigns against FGM/C, says.

Helwana, Arif, Kyai Ali, and Suci now actively use a range of public fora, both social and religious, to educate community members in their respective areas to abandon FGM/C. With their leadership at the community level, along with multi-sectoral efforts nationwide, ending harmful practices - even those as entrenched as FGM/C - is not just a pipe dream.

For more on how UNFPA and partners address FGM/C, visit https://www.unfpa.org/FGM and https://www.unfpa.org/unfpa-unicef-joint-programme-eliminate-female-genital-mutilation