By Peter Bittner

On July 8, hundreds of people gathered in Mongolia’s Government Palace to launch the nation’s #HeForShe Campaign. #HeForShe is an international movement for gender equality led by the United Nations in support of women’s rights.

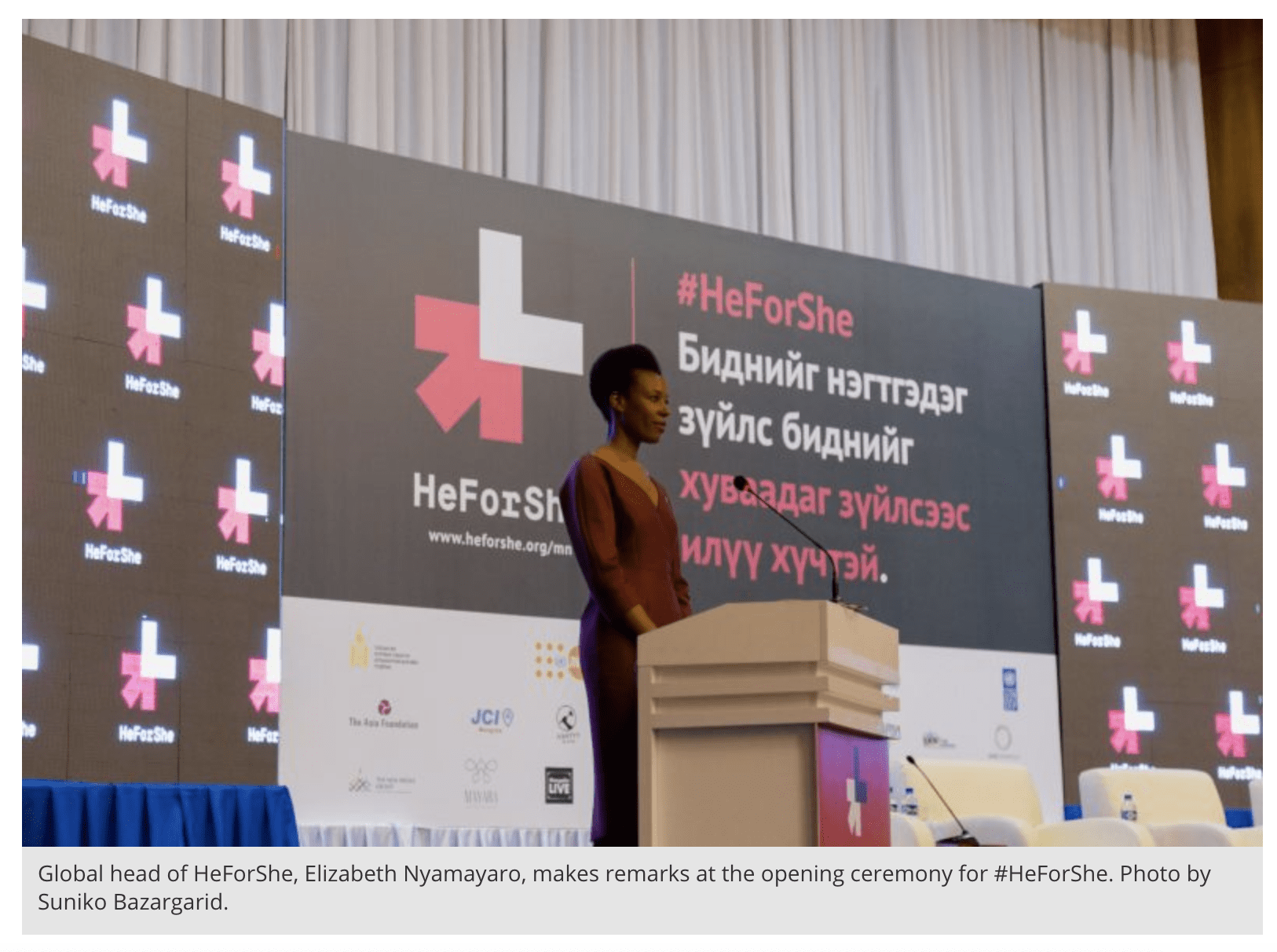

According to Elizabeth Nyamayaro, global head of the #HeForShe movement, “We started #HeForShe in 2014 with the realization that men are half the world’s population but they hold the majority of the power. We started to look at the way that men can become part of the solution.”

In recent months, the landlocked nation between China and Russia has grappled publicly with issues of gender inequality. Vast inequities exist between men and women in Mongolia, resulting in power imbalances that lead to fewer women in decision-making positions and, worse, high levels of gender-based violence (GBV).

“In general, Mongolian women have the same opportunities as men,” said Munkhsoyol Baatarjav, an economic consultant who ran for parliament in the 2016 elections. “However, in reality, due to the women’s social status, economic and financial capabilities there are plenty of disadvantages for women to take leadership positions both in the political and corporate world.”

Data suggests a strong glass ceiling exists for Mongolian women. According to the UN, in the private sector less than 15 percent of women hold senior-level management positions. Only 17 percent of the seats in Parliament and two ministerial cabinet seats are filled by women, with no women holding the positions of governor or state secretary as of 2016.

“In politics there’s lots of sexism. Women don’t have the funds to run for office,” said Ts. Azjargal, a prominent activist and emcee for the #HeForShe campaign kickoff event. She says that women can also hold themselves back due to their mindset, a product of predominant cultural norms regarding gender roles.

“We need to know that we’re qualified to have leadership positions. Women should support each other,” said Azjargal.

Since Mongolia’s transition from Soviet-era socialism to democracy in the early 1990s, families in the countryside have been more likely to send their daughters to study or work in urban areas. Girls are seen as more expendable than boys, who are required to help with the intensive labor of herding. As a result, more than 60 percent of university students are female, which is reflected in the workforce. Mongolian women are generally higher-educated and more likely to be employed than men.

Yet, despite this reverse gender gap, Mongolian women have struggled to attain leadership posts at the highest levels across most fields. This can be attributed to Mongolia’s traditional patriarchal norms. Old adages such as “she’s better than a bad man” or “her intelligence is short but her hair is long” are reflections of a devaluing of women’s competencies outside of child-rearing and homemaking roles.

The #HeForShe movement takes aim at these deeply-seated structural inequalities by calling on men to be fully involved in working together to challenge and redefine masculinity.

“In order to address these inequalities in Mongolia, I must again emphasize that it cannot be achieved by women alone,” said Naomi Kitahara, United Nations Population Fund Representative and Chair of the UN Theme Group on Gender in Mongolia.

So far, over 700 men in Mongolia have signed the #HeForShe pledge to be outspoken allies for women. One of the foremost goals of the program is to create a community of men empowered to combat gender-based violence (GBV) by holding one another accountable.

“Fighting for gender equality starts from speaking out against abusers,” said Bolorsaikhan Badamsambuu, a member of Men4Change, an initiative to start a public discourse on gender equality led by men.

Up until recently, very little has been known about the prevalence and patterns of GBV in Mongolia. However, the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) and the National Statistics Office (NSO) of Mongolia released a report in June with the findings of the first nationwide survey on gender-based violence. The survey, covering more than 7,500 households, has revealed extremely high rates of violence against women across the country. Mongolia’s rate is among the highest in Asia.

The study found that among ever-partnered women, 58 percent have experienced at least one type of violence or controlling behaviors including physical, sexual, emotional, or economic abuse. It also revealed that 31 percent have experienced physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime. Perhaps most alarming are the views on violence that women hold themselves. One in four women, regardless of her social and economic status, agreed that “a husband may beat his wife if she is unfaithful.”

“People think that it’s an Oriental tradition. There are sayings in Mongolian that you should beat your wife once a month,” said Lkhagvadulam Ch., a member of the research team. “People need to know that it is not acceptable.”

The study’s surveyors overcame serious challenges ranging from arduous off-road travel and difficulties locating interviewees, many of whom were nomadic, to the emotional and psychological impacts of bearing witness to women’s traumatic experiences.

“It was not easy to ask the questions. The questions were so personal. But we had to know,” said one research team leader who preferred to by identified only as Nyamsuren.

“They would cry sometimes – the interviewers and the survivors. Sometimes both,” she said.

While data concerning reported crimes has been recorded for years at the national level, the rates of reporting have been very low. The new UNFPA/NSO report suggests that only about 1 percent of crimes of violence against women are reported to authorities, according to Ariunzaya Ayush, chair of the National Statistic Office.

“The most important thing is to have the correct, real data about the violence. This gives the government the information it needs for next steps,” said Ayush.

A. Undraa, a member of parliament, said, “the rights of women and girls is an issue of human rights. In Mongolia, rights of men and boys are often violated too. Therefore, gender equality is a multi-faceted issue and it is an issue of quality of life.”

“In 2018, we have the real possibility of addressing power relations between men and women, and it is our generation’s responsibility to do so,” said Phumzile Mlabo-Ngcuka, executive director of UN Women.