Bjorn Andersson is the UNFPA Asia-Pacific Regional Director. This op-ed was originally published by the Thomson Reuters Foundation, a UNFPA Asia-Pacific media partner, on the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation, 6 February, 2020.

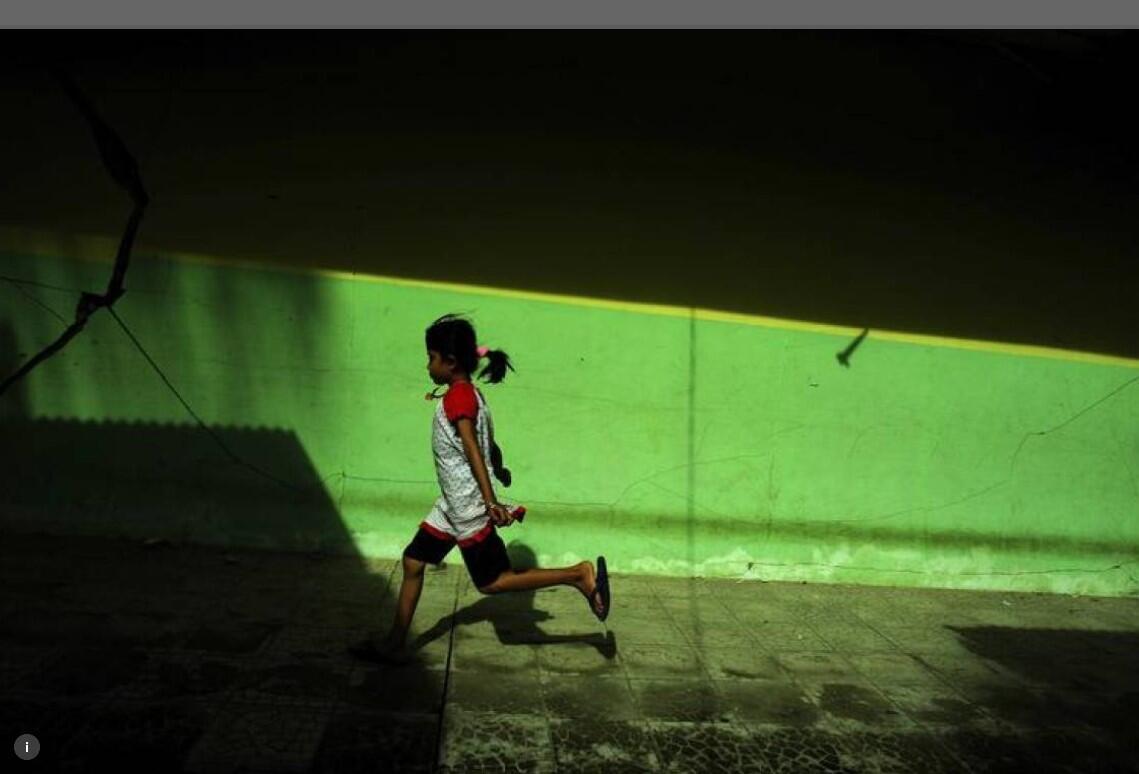

"Reach perfection through circumcision," promised the ad on the Facebook page of a community organisation in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Parents were invited to bring their daughters to a mass ceremony where the procedure would be performed for 100,000 rupiah - or even less for those who couldn’t afford the equivalent of $10.

Event organisers said more than 100 girls between the ages of one and 14 had been signed up for the procedure which many families believe is a religious requirement that also benefits the health and wellbeing of women and girls.

Nothing can be further from the truth.

Female genital mutilation (FGM) and cutting – so-called "female circumcision" -- not only has no medical value whatsoever, it’s one of the most egregious human rights violations that exists today, reflecting deep gender inequality and an extreme form of discrimination and violation of the rights of girls and women.

The practice stubbornly persists across many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and Asia – where it’s witnessed either on a wider scale or in select communities. Across Asia, this includes Brunei, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, Philippines, Maldives, Sri Lanka and Thailand.

In Asia, FGM typically involves pricking, piercing, scraping or cauterizing the genital area. Procedures practiced elsewhere are even more invasive and horrific. But this is not a question of degree -- any type of mutilation of the female genitalia is a human rights violation.

There’s a concrete target to eliminate FGM by 2030 under the Sustainable Development Goals which all countries have pledged to achieve. However, ending a tradition steeped in religious trappings is far easier said than done.

Even in countries with laws aimed at ending FGM, the practice often continues largely unchecked - either through traditional service providers in rural areas, or, increasingly, through clinics and hospitals in urban centres where the procedure has become medicalized, often performed routinely at birth.

What must be done?

All governments should actively commit to "zero FGM" in both policy and practice as a priority under their efforts to achieve commitments under the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population Development (ICPD) and the SDGs. These efforts also require the need to gather better data on FGM, including the full extent of prevalence. Revealing this should spur ministries to work together on a coordinated response – including health, women and child protection, education and national human rights institutions.

Existing policies must be reviewed and revised to ensure that laws banning the procedure are explicit. And enforcement of laws must be effective and pervasive. In tandem with legal enforcement, education is an equal priority, particularly amongst health sector practitioners. FGM’s harms must be included in curricula for doctors, nurses and midwives. This has begun to occur in some countries – such as Indonesia, where the national midwives’ association is at the forefront of helping eradicate FGM.

Perhaps the most important factor in eliminating FGM is the need to change the hearts and minds of parents, families and entire communities. This cannot occur without the active engagement and the help of religious and cultural leaders. It is often that messages grounded in scripture, delivered by community leaders, have significant influence in shaping how families and societies think and act.

Significant success has already occurred through initiatives which include working with faith and community leaders in targeting child marriage and domestic violence. Incipient signs of success are evident from using this same inclusive approach in tackling FGM.

There’s also emerging evidence that women who themselves suffered FGM are increasingly refusing to allow their daughters to be similarly harmed. As well, more and more men are realizing the harm that FGM has caused their wives, and they are motivated to ensure their children don’t suffer the same cruel fate. It’s clear that as authentic awareness of the harm of FGM increases across societies, we will collectively achieve better outcomes over time.

But time is not on our side. Some 200 million women alive today have already been mutilated – with 4.1 million girls around the world at risk this year alone.

With the clock ticking, it’s time to muster our collective will and take concrete action to convert commitments into reality, safeguarding the futures of the millions of girls at risk of FGM today and preventing a lifetime of harm.

"The true character of a society is revealed in how it treats its children." This profound wisdom from Nelson Mandela should inspire our efforts to eliminate female genital mutilation and relegate this insidious procedure to the annals of history.

A new joint study from UNFPA and Johns Hopkins University indicates that eliminating female genital mutilation in 31 priority countries globally by 2030 would require an investment of $2.4 billion, for programmes aimed at prevention, protection. and care and treatment.