“We do not expect anything because this service is committed from the heart”

“We do not expect anything because this service is committed from the heart”

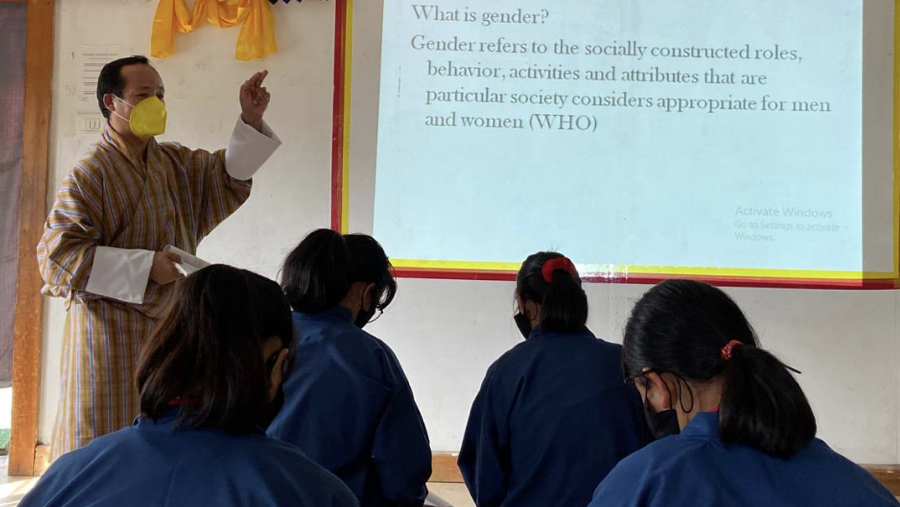

Thinley Namgyel is a school vice principal and teacher in Trashigang district in the eastern part of Bhutan. He is also a community based volunteer who is specially trained to handle cases of gender-based violence. He works with the local police and community leaders to ensure survivors of domestic violence get the support and protection they need.

“I already have an enormous amount of workload as a teacher,” Thinley says. “But as a human being, you must commit to service for others. So that sense of volunteering in Buddhism has compelled me to do this service, even though it is very challenging.”

Thinley deals with difficult cases of gender-based violence, often involving phone calls after school hours, so he has to be careful to keep his conversations discrete and separate from his family life.

"As a human being, you must commit

to service for others."

“If I take this issue home I can traumatize my family members,” he says. But holding the painful stories can be difficult because he cannot even confide and share cases with his other half because of the strict protocols around privacy and protection of the survivors' identity.

Thinley says the sensitive nature of the cases and a culture that is not open to talking about violence makes the work even more challenging.

“Bhutanese people by their nature are very closed,” he says. “We are not that open to new ideas, some do not have exposure to come out of their self-isolated cocoons. People do not want to speak out about what problems they are undergoing.”

Thinley started to notice the warning signs through his work as a teacher and his close contacts in the community and with students.

“Many women and children in Bhutan undergo a lot of trauma at home,” he says. “So in this situation, I thought, “why not someone like me who understands the hidden problems of people in our society come out and help those in need of such services?’”

Thinley wanted to do something to help these women and children have a voice. “If they are to face these challenges of violence,” he says, “at least I will voice their concerns, I will speak on their behalf and I will bring their problems to the notice of authorities for intervention.”

"I will speak on their behalf and I will bring their problems to the notice of concern authorities for intervention.”

Thinley says Bhutan remains a deeply entrenched patriarchal society with strong gender biases. A lot of his time is spent building relationships with community leaders who are mostly males themselves so they know how to identify and respond to cases in their communities.

“Sensitization of advocates takes time,” he says. “It takes time to build these relationships. Those meetings are not scheduled, we just have to get these people on our side.”

“When a case is reported to me, I try to connect with these people, the different stakeholders in the communities,” he says. “Intervention is not always possible, going myself into the field, getting them and rescuing them from danger is not an ultimate option.”

Limited services for domestic violence survivors and the close knit nature of the communities in Bhutan makes each case a challenging balancing act. “Normally we sit with the community leaders and talk to them about how to involve authorities in the case. I am pleased that through these discussions we help the survivors who are trapped in domestic violence situations.”

"We sit with the community leaders and talk to them about how to involve authorities in the case."

The pandemic and movement restrictions made it difficult to respond to cases in the traditional way. “What I could do in-person was very minimal because of the movement restrictions. I managed to do the work collaboratively through calls based in my station.”

This transition from in-person meetings to telephone- based support has been a big shift for Thinley but he says the calls in many cases have resulted in tangible actions.

Thinley says he sometimes deals with survivors in moments of terror and extreme distress. He says it’s rare, but occasionally he gets follow-up calls from survivors to let him know they are okay. “From time to time people call and they say: ‘Because of you, today I am safe. I'm happy that I have been rescued from that difficult situation.’”

“From time to time people call and they say: ‘Because of you, today I am safe. I'm happy that I have been rescued from that difficult situation.’”

He says these calls keep him motivated, especially when the stress of doing the right thing for each caller creates ongoing tension as he tries to get them support.

“We do not expect anything because this service is committed from the heart,” he says. “When you get to hear those responses, you feel so happy. That is the reward. They do not happen often but sometimes we get lucky to hear the echoes of our own love, care, support and consolation through those people whom we have touched.”

Thinley is one of 300 registered community based volunteers across 20 districts in Bhutan with UNFPA's partner organization RENEW.

This work was made possible through funding from the Government of Australia, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) in support of a regional COVID-19 project implemented by UNFPA and partners.

Learn more

The Inter-Agency Minimum Standards for Gender-Based Violence in Emergencies Programming

Pandemic and rising tide of violence increase demand for mental health, psychosocial care in Bhutan

We are frontline GBV responders: Supporting survivors of gender-based violence during COVID-19