Strides made in South Asia show that eradicating obstetric fistula is within reach

As countries spanning the globe race to eradicate obstetric fistula by 2030, progress made in Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan in tackling one of the most serious injuries of childbearing offers hope and a blueprint for others.

When Dr. Shershah returned home to Pakistan from his medical training in the UK in early 1990s he knew next to nothing about obstetric fistula, which is one of the most serious injuries of childbearing.

“I was hoping to open an in vitro fertilisation clinic. But once I arrived at the government hospital and I saw what fistula was, I got very upset. I felt useless,” the veteran surgeon recounts one December afternoon from the city of Atlanta in the US, where he’s been fundraising for his Pakistan-based hospital.

Obstetric fistula is a tear between a woman’s vagina and rectum or bladder caused by complicated or prolonged and obstructed labour, and it causes chronic incontinence of urine or faeces.

UNFPA estimates that over 500,000 women in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa are living with fistula, and each year between 50,000 to 100,000 women worldwide are affected by the condition. The UN agency has spent the last two decades spearheading the global Campaign to End Fistula by 2030, through prevention, treatment, social reintegration of survivors and advocacy.

Intrinsically linked to child marriage, obstetric fistula prevents women and young girls from fully participating in society, and can lead to chronic medical issues. Many cannot work, some cannot move. More often than not, women with the condition suffer in silence and isolation, shunned by their families and communities.

Because the injury is often accompanied by stillbirths, scores of women experience serious mental health impacts due to the loss of their child and the physical and social aftermath of obstetric fistula.

But just like maternal mortality, obstetric fistula is entirely preventable with the right health care system interventions and change in cultural attitudes towards and among women. That’s what Dr. Shershah has been striving to accomplish.

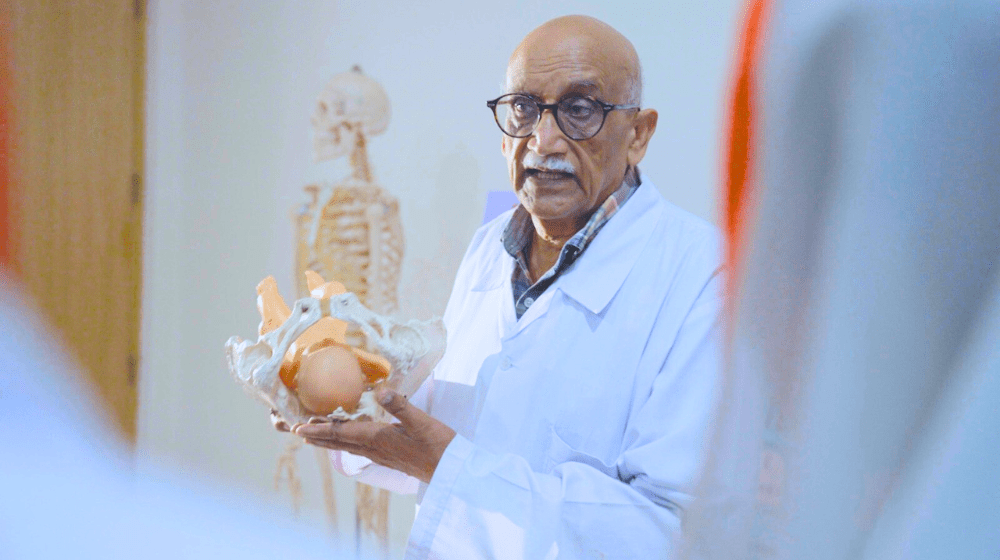

Back in the 90s, after a six months fellowship in Ethiopia, where he learnt how to operate fistula, Dr. Shershah went back to Pakistan, where he’s been treating women and girls suffering from the condition ever since.

Initially working at government hospitals, Dr. Shershah decided to divert his entire attention to helping women and in 2006 he set up the Koohi Goth Women Hospital, a 200-bed health centre in the southern metropolis of Karachi, where services are provided free of charge.

In a country, where annually up to five thousand women are affected by fistula, his facility – operating thanks to private donations and grants from organisations like the UNFPA – treats up to 1,100 fistula patients each year.

The facility is also a training ground for fistula surgeons and midwives, known as skilled birth attendants. Over fourty surgeons from across Pakistan have learnt how to surgically treat obstetric fistula at the hospital to date. “So now we have nine [medical health] centres where our surgeons are working,” Dr. Shershah says.

But this is not enough to eradicate obstetric fistula. “The problem is, we are able to treat fistula but we are not able to stop the fistula making factories,” the surgeon says, referring with a metaphor to all those factors that lead women to develop fistula in the first place: poverty, lack of access to health care, poor quality of services, and delays in referrals.

Aside from putting a stop to child marriage and improving access to education for girls, Pakistan needs a legion of midwives at village level. While Dr. Shershah’s clinic trains up to 200 skilled birth attendants each year, that’s just not enough to assist women in the country’s eighty thousand villages.

Midwives are essential to obstetric fistula prevention as they attend home births at the village level, making them safer for women, helping identify existing fistula cases and supporting referral for treatment.

Authorities in Bangladesh and Nepal have also prioritised this form of public health system intervention with astounding results.

“It all started in the village. We’ve got family planning health workers, midwives and all of them are trained, with field workers going door to door, they also do family planning. In Bangladesh, we have skilled diploma-graduated midwives, so most deliveries are with skilled birth attendants, at the union level facility by the midwives” says Dr. Anowara Begum, Bangladesh’s veteran obstetric fistula surgeon, who has been helping women since the 1980s.

Because of initiatives by the Government, supported by UNFPA, like surgeon training in caesarean section, awareness raising campaigns at village level and the mass training of midwives, the number of obstetric fistula patients has plummeted over the years, according to Dr. Begum.

While there is a dearth of reliable data pertaining to actual obstetric fistula, Dr. Begum points to the fact that these days most women seeking treatment at specialist centres don’t suffer from obstetric fistula but other ailments. “Another thing is that some fistula centres have disappeared because the number of patients have gone down so much,” she adds.

And so today Dr. Begum is optimistic. “I think it will be possible for us to eradicate obstetric fistulas by 2030 in Bangladesh,” she says.

Such a scenario could also play out in Nepal, where the authorities have rolled out similar interventions, but Nepal’s number one obstetric fistula surgeon Dr. Mohan Regmi is concerned about a worrying global trend: decrease in funding.

“If you look globally, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic, the allocation of funding for fistula is going down,” says Dr Regmi, founder of the B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences (BPKIHS) in eastern Nepal. Located in Dharan, a city at the foothills of the Himalayas, it is the only facility in the area successfully treating obstetric fistula.

Without sustained funding, which is essential to ensuring quality delivery services, pre and post-natal check ups and to keeping skilled obstetric fistula surgeons motivated in treating fistula patients, progress might stall, Dr. Regmi posits.

Perhaps most importantly, he says, lack of funding would have an immediate impact on his potential patients. “My patients come from vulnerable backgrounds, so the economic barrier will be the most prominent barrier preventing them from coming into the hospital,” he says. “If that [economic] barrier is overcome, they will come to the hospital for treatment. So it's very, very important that they are funded for the treatment.”