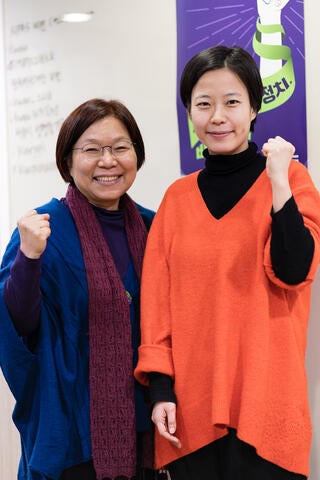

Seoul, Republic of Korea - Youngsook Cho sits in the book-strewn top floor of a building dedicated to women’s rights.

The six-story building in Seoul, the capital of the Republic of Korea, houses a variety of women’s groups, explains Cho, one of the leaders of the feminist coalition Korean Women's Associations United (KWAU).

“Each group has a different issue and a different agenda,” she says, “but when we need to change laws, policies and programmes, we need to unite together.”

She knows from experience the power of collective action.

She and other activists spent decades working, successfully, to transform the country’s deep-seated cultural preference for sons. In fact, the Republic of Korea is one of the only countries in the world to have faced extremely high levels of sex ratio imbalance – the result of families selectively aborting female foetuses – before completely eliminating this imbalance. The feat is even more remarkable considering that it was accomplished within a single generation.

Prior to the 1980s, son preference was widespread, but sex ratios were not significantly skewed. Instead, couples were often pressured to have children until they bore sons.

“I was born in 1961. My parents had five children; I have an older sister and a younger sister, and the last two were boys,” Cho recalls. “My mother used to say that if she didn’t end up having boys, she would have been abandoned by her mother-in-law.”

Patriarchal laws and norms meant that only sons could perform ancestral rites or inherit their families’ fortunes. When daughters married, they were expected to support the rituals of their in-laws rather than their own families.

“My grandmother used to scold my parents, ‘Why do you invest in the girls? The girls are useless when they get married’,” Cho says.

As the country underwent rapid development, household income increased, education expanded and health improved. The Government also created tax and housing incentives to encourage smaller families.

By the 1980s, “people were better off,” says Dr. Eun Ha Chang, a director at the Korean Women’s Development Institute, a Government research body. At the same time, “they were introduced to foetal sex screening technology.”

Abortion had long been illegal, “but in reality, abortion was very much common among women,” Cho explains. “I know many of my friends had to have abortions because of their parents-in-law… It was a kind of control over women’s bodies, but they didn't recognize it as a violation of women's choice at that time. The general public just agreed and accepted.”

Driven by sex-selective abortion, the country’s sex ratio grew increasingly skewed in favour of boys. Alarmed, officials banned pre-natal sex testing in 1987 and released a public awareness campaign about the dangers of the girl shortage in the 1990s. Yet the imbalance only continued to grow. By 1994, 115.4 boys were born for every 100 girls.

But the cultural preference for sons began to disappear. One key factor, Chang explains, was the transformation of the economy from a rural agrarian one to an urban, industrial one.

“Sons are usually more preferred in agrarian societies,” she says. Also crucial were the investments being made in women’s and girls’ education, “which led to women's consciousness about gender equality… the very strong women's movement in South Korea then triggered changes in laws and policies.”

Cho’s own experience bears this out. “I entered the university in the time of the 1980s. It was a radical environment in all the universities. I studied social science, and I realized the structure and root causes” of son preference.

She went on to work with women’s groups that, together, pushed for a raft of policy changes. The 1980s and 1990s saw dramatic reforms, including laws that granted inheritance rights to women, laws taking on employment discrimination and domestic violence, and eventually, in 2005, legal changes enabling women to serve as the heads of their households.

Kyung-Jin Oh, a young coordinator at KWAU, saw the last vestiges of son preference as she was growing up in the 1990s. Her mother was the object of pity for not having sons, she recalls.

“People said to my mom, ‘Oh, you have three children already, but you have only girls. What are you going to do?’”

Girls were also a minority in her elementary school classes: “If there were 50 students in a classroom, we saw that 30 would be boys and 20 would be girls.”

Today, the echoes of sex ratio imbalance can be felt in the attitudes of some men facing a disproportionately small dating pool of women, she says. “Many men feel that they do not have their own female partners to get married to or to date.” In the worst cases, these frustrations can result in gender-based violence. “We also see some killings of women,” she says.

Oh is inspired to follow in the footsteps of the activists who came before her.

“I have a lot of respect for our senior feminists. Korea was very poor, and we didn't have an established democracy. There were so many agendas worth fighting for, for example, human rights, democracy and economic development. It must have been very difficult for activists to focus on women's rights issues. You can see now we have a fruitful and active women's rights movement across the country, but we would not without the legal legacy and experiences of the older women’s movement.”

Today, the sex ratio of babies born in the Republic of Korea has reached natural levels, and a vibrant new generation of feminists has entered the national stage. These younger activists are battling new forms of gender-based violence, such as the proliferation of spy-cams used to create and distribute nonconsensual pornography, and they are challenging conventional beauty norms with the #EscapeTheCorset movement.

“They are more vocal,” says Chang. “Girls as young as middle school students are actively involved in the #MeToo movement… We’re watching carefully how this young feminist movement will lead to the future.”

Cho agrees. “The young generation, they can take over. They can use their technology and their new ideas, and they can change all things.”

VIDEO: Youngsook Cho's experience working to reverse the high sex ratio at birth in the Republic of Korea.

Learn more about combatting harmful practices including this story in “Against My Will,” UNFPA’s flagship State of the World Population Report 2020, launched June 30.

Take an in-depth look at the drivers, consequences and ways forward to end child marriage, female genital mutilation, son preference and gender-biased sex selection once and for all.