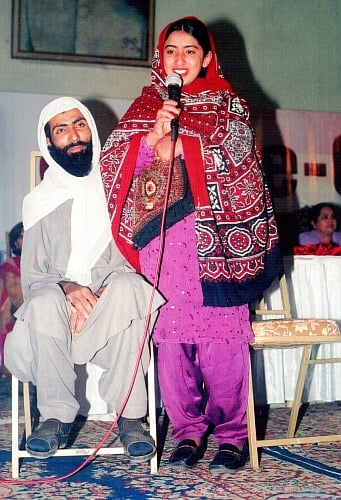

It was personal experience that turned Gul Bano and her cleric husband, Ahmed Khan, into ambassadors against early marriage and its worst corollary—obstetric fistula.

As is the custom in the remote mountain village of Kohadast in the Khuzdar district of Balochistan province in Pakistan, Bano was married off as soon as she reached adolescence, at 15, and was pregnant the following year.

There being no healthcare facility near Kohadast, Bano did not receive antenatal care and no one thought there would be complications. But, events were to prove different. After an extended labour lasting three days, Bano delivered a dead baby. “I never saw the colour of my son’s eyes or his hair. I never held him once to my bosom,” recalls Bano, now 20.

Her troubles had only begun. A week later, Bano realised she was always wet with urine and reeking of fecal matter. “I was passing urine and stools together.”

Unable to handle the prolonged labour, Bano’s young body had developed an obstetric fistula caused by the baby’s head pressing hard against the lining of the birth canal and tearing into the walls of her rectum and the bladder.

Obstetric fistula is now generally acknowledged to be another burden on the girl child, deprived of basic education and forced into marriage—for which she is neither physically nor mentally prepared.

Khan stood by his young wife and sought medical help. He discovered a hospital in Karachi specializing in treating fistula and other conditions related to reproductive health. Koohi Goth Women’s Hospital, where fistula victims are treated free, was started by Dr. Shershah Syed, one of Pakistan’s first gynaecologists to train in repairing the painful and socially embarrassing condition.

“It’s been almost three years and she [Bano] has gone through six operations,” says Dr. Sajjad Ahmed, who worked at Koohi Goth as manager of UNFPA’s fistula project from June 2006 to February 2010.

Today Bano and Khan have become vocal advocates of the campaign against fistula. They travel across Pakistan, spreading the word about how to prevent the injury and what to do about it. “Khan is a cleric and yet he does not conform to the stereotype of a religious person,” said Syed. “He tells parents that fistula can be avoided if they stop marrying off their daughters at a very early age.” Bano shares her story and tells married women about the importance of birth spacing, antenatal checkups and timely access to emergency obstetric care.

—Zofeen Ebrahim, Inter Press Service