The world is facing an unprecedented number of compounding crises - disasters, conflicts, and the ongoing impacts of climate change. These emergencies disproportionately affect women, girls in all their diversity, exposing them to heightened risks and delays in seeking life saving maternal healthcare for pregnancy and birth complications and gender-based violence, while also limiting their access to essential health services.

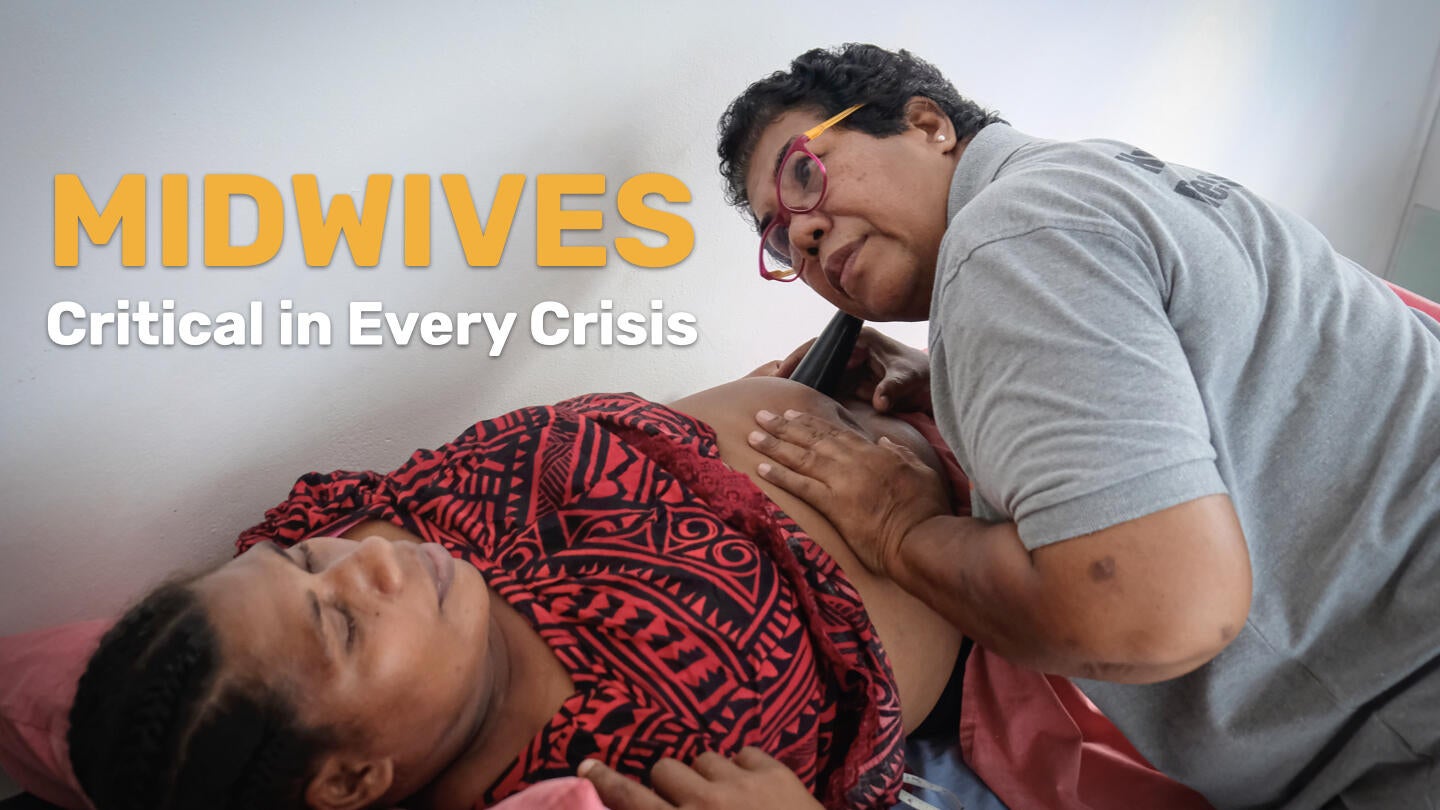

Midwives are trusted first responders within their communities, playing a vital role in strengthening health systems to be resilient to crises. They can provide up to 90 per cent of sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, and adolescent health services, even in the most complex humanitarian settings.

A global shortage of nearly 1 million midwives, a regional shortage of over 200,000 in Asia Pacific, and a lack of international commitment to invest in their training, development, deployment and support, limits their reach and endangers women and girls who rely on them for care.

This collection of profiles from around the region presents a snapshot of a few of the millions of midwife heroes who stand on the frontlines of climate impacts and humanitarian emergencies, coping with daily crises that affect women’s health and dignity.

Philippines

”Whenever there is conflict, families flee,” says Rhiana. “They go to evacuation centers or go stay with extended family and some people stay in their vehicles.”

As a midwife in the conflict-affected province of Mindanao, Rhiana is familiar with the cycles of insecurity and recovery that mothers are struggling with. Her own experience with displacement has shaped her compassion: “When we came back to our house everything was destroyed,” she recalls. “Our savings were taken, we had nothing left.”

Rhiana‘s education has been marred by the conflict that has endured for decades in Mindanao.

“There was a time when I couldn’t even go to school because I couldn’t cross the conflict zone.”

Rhiana began her journey as a volunteer facilitator at a Women-friendly Space supported by UNFPA and the Government of Australia. The spaces are a refuge for women to connect with other women and get support. She was trained in how to be an effective frontline advocate for women affected by the protracted crisis. The modest stipend she received helped her pursue her studies to become a midwife.

Rhiana is now a fully qualified midwife and works at a birthing clinic with local health officials. As a midwife she has to operate in dangerous situations, frequently travelling to remote forest camps where she provides care to adolescent mothers whose partners are affiliated with armed groups.

|

|

“It’s definitely difficult to reach these young mothers, but they need a midwife,” she says. “If I'm visiting a patient in a secluded area, my mother or my husband comes with me.”

She says many patients have a difficult time getting to the rural clinic. ”There are armed groups along the road that intimidate women from coming to health appointments. Women say they are in a conflict area and they can’t get to the clinic.”

Rhiana continues to go out into the community, advocating for family planning and safe motherhood with the local health teams.

“Even in a conflict, women still give birth,” she says. “We need to have a safe place for them to give birth.”

Apart from armed violence, natural hazards like floods are another barrier women in Maguindanao frequently face in accessing quality sexual and reproductive health services. “Flooding is a disaster that we often experience in Mindanao. I regularly have to cross a flooded river to get to patients.“

Despite the challenges, Rhiana says she is seeing real progress. “There have been a lot of changes to my communities since I joined. Women are much more aware of how we can support each other to get through this crisis.”

Afghanistan

Habiba is a midwife at the Family Health House in the remote village of Taiwara. The village in Herat province has a population of 15,000 and has long been cut off from essential health services due to its challenging terrain and complex environment.

”My passion for midwifery started when there was no midwife doctor or clinic in our village,” she says.

“Before this centre was built, mother‘s faced many challenges, often losing their lives and their children.”

Habiba now provides life-saving health services to women and girls, especially in times of crisis. With support from UNFPA, she completed her midwifery training and continues to receive ongoing support to keep the health centre stocked with vital medicine and supplies.

“I have three daughters,” Habiba says. “I dream that all of them will become midwives to continue this mission.” WATCH THE VIDEO

Mongolia

For nearly four decades, Batkhuu has been a lifeline for mothers in Erdenesant Soum, Tuv Province of Mongolia. With 38 years of experience as a midwife, she has weathered fierce winters, floods, and long, treacherous journeys to ensure that mothers and babies receive safe, timely care

“The profession of midwifery requires a lot of responsibility,” Batkhuu says. “It’s not just about skills. Your personal attitude must be the right one.”

In Mongolia’s remote regions, where healthcare services are limited, midwives like Batkhuu are often the only trained professionals who can manage childbirth and provide emergency obstetric and newborn care. “This winter, we traveled 12 hours through heavy snowfall. Sometimes the car broke down, or we ran out of gasoline. At times, I had to borrow a horse to reach a patient,” she recalls. In the summer, flooded rivers cut off entire communities.

“You can see your patient across the river, but you can’t get there. Still, we find a way.”

Despite the hardships, Batkhuu’s dedication never wavers. “I feel very grateful and satisfied when a baby is delivered safely, and the mother has no complications,” she says with a smile. “I think my job is the best because it brings happiness to families.”

“It’s impossible to imagine life without a midwife in rural Mongolia,” Batkhuu says. Her story is a powerful reminder that in times of crisis, midwives are not just healthcare providers — they are beacons of hope.

Myanmar

In the immediate aftermath of the devastating earthquake in Myanmar on 28 March 2025, essential services, including health services, were disrupted, leaving women and girls—desperate for urgent assistance. Amidst this chaos, midwives emerged as frontline heroes, providing hope and life-saving support for the women of affected communities.

“Women, especially pregnant mothers, were severely impacted,” says Yu Yu, a midwife who endured the earthquake.

“Women faced uncertainty about where they could safely deliver their babies. Healthcare facilities were destroyed, services disrupted, leaving pregnant women stranded and vulnerable.”

In these challenging conditions, Yu Yu took extraordinary measures. “When women can’t reach us, we go to them,” she says.

A mother Yu Yu regularly cared for was suddenly stranded, unable to reach any clinic as her labour pains intensified. She rushed to the woman’s location, confronting physical obstacles and emotional challenges as the series of aftershocks hit Mandalay.

Bangladesh

“It was a complicated case,” says Sumana, “But both mother and child are safe now, and that’s all that matters.” Sumana Akter is a midwife in one of Cox’s Bazar’s refugee camps. For many Rohingya women living in the camps, access to maternal healthcare can be uncertain. Travel is not always safe. Emergencies often occur at night. And the stigma around seeking facility-based care still persists.

In this context, midwives aren’t just health workers—they are the backbone of maternal survival. “Every shift brings something different,” Sumana says.

“One minute you’re helping with a routine delivery. The next, it’s a high-risk emergency. There’s no time to think twice.”

At the Friendship Hospital, supported by UNFPA, the maternity ward is full. “In this humanitarian setting, midwives are always needed,” she says. “Most women arrive already in pain, some after long delays. Every second counts.”

“When a mother holds her baby for the first time and smiles through her tears, “ says Sumana, “that’s the moment I live for.”

Solomon Islands

Esther is a midwife at the National Referral Hospital in Honiara, where she plays a key role in expanding emergency obstetric training for midwives in the provinces.

“It’s really important that women in the provinces can reach a midwife who is trained to deal with complications,” she says.

“Sometimes the weather is bad and the sea is rough so getting on the boat to come here is difficult, especially for a pregnant mother in an emergency. It’s important that midwives can handle complications and know when to refer cases to us here in Honiara.”

The Solomon Islands is grappling with an overstretched health system, a rapidly growing young population and the increasing impacts of climate change. Esther is on the frontline of these intersecting challenges as a health professional providing emergency care in a system that is often overcrowded and always under-resourced. “Sometimes we have three women in a single bed here in the referral hospital. They only can stay for eight hours because the ward is busy and we need the space.”

Indonesia

Indra Supradewi is a midwife with decades of experience responding to some of Indonesia’s most devastating disasters. A longstanding member of the Indonesian Midwives Association (IBI) since the 1980s, she has served in crisis affected areas including Aceh after the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami; Yogyakarta, West Sumatra, West Nusa Tenggara, earthquakes in 2006, 2009, and 2018; Palu following the Sulawesi earthquake and Tsunami in 2018; Lumajang after the Mount Semeru volcanic eruption in 2001; and the Cianjur earthquake in 2022.

“At first I didn't imagine I wanted to be a midwife but after I saw it, I understood I love it,” says Indra.

“Midwives accompany women in reproduction: this is shaping the generation of the nation. There is no better way to stand by women."

“A healthy start for the next generation is determined by the health of women so that means we have to take care of our own health,” she says. “In normal situations there are many pregnant women, this becomes critically important in disasters.,”

When a 7.5 magnitude earthquake struck Central Sulawesi on 28 September 2018, triggering 1.5 metre tsunami waves that caused widespread damage and destruction to the areas of Palu and Donggala, Indra was among the first responders.

The disaster affected 2.4 million people, and over 191,000 people were in need of immediate humanitarian assistance. Amid collapsed infrastructure and overwhelmed services, she worked to establish safe birthing centers to support pregnant women.

“Every birth carries risks, but in a disaster, those risks multiply,” Indra says.

“In a disaster situation, access to services is cut off, the roads are damaged, the electricity is out, You can imagine what it's like to have to give birth.”

She recalls how fear and displacement triggered premature labor in many pregnant women. “When you have premature labour there are so many complications and then you give birth into a health system that is destroyed.”

Indra also points to the rise in gender-based violence (GBV) in the wake of disasters. “The risk of gender based violence, including sexual violence, escalates during a crisis, especially in overcrowded tents and shelters. In Palu, we saw many GBV cases. It’s not just about childbirth—comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services remain a critical need, even in the most unstable conditions.”

“Hopefully there will be no disasters, but we know there will be more,” she says.”The most important thing is coordination, so when we are ready but when it happens in the field, coordination must still occur, that's why we have to create teams, plan and prepare. ”

Philippines

Anita is a midwife-nurse in the suburb of Santa Rosa, on the sprawling outskirts of Metro Manila. In 2021, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, her local birthing clinic received an electric Reproductive Health bike (RH Bike) from UNFPA, through the support of the Government of Canada. The bike was introduced to bridge critical gaps in maternal care, especially when it made it nearly impossible for pregnant women to visit health centers for prenatal care. She says the electric bike has changed the way she delivers sexual and reproductive health services —from maternal care to family planning—especially in emergency situations.

“The streets are small and narrow so it allows us to get into communities to host talks with young people,” Anita says.

“When we turn up, we have conversations about teenage pregnancy, sexual reproductive health, safe births, gender-based violence. So many more people come because we are in their neighborhood, and they don’t have to come to see us at the clinic."

The electric bike is easy to operate, doesn’t require additional drivers or fuel, and can be deployed on short notice. Powered by a battery that lasts about two years- some models are being tested with solar panels- it is a practical energy-efficient tool for emergencies and outreach. “When women say they can’t make it to their prenatal check-ups because of transportation issues, the bike even allows us to help women to and from their appointments to ensure they get the care they need for healthy outcomes for their children.”

The electric bike can carry family planning commodities, bringing both information and essential services closer to the community.

Learn more:

- UNFPA on Midwifery

- UNFPA Midwifery Dashboard

- Minimum Initial Service Package - The minimum, life-saving sexual and reproductive health needs that humanitarians must address at onset of an emergency

- GBV Area of Responsibility brings together non-governmental organisations, UN agencies, academics and others under the shared objective of ensuring life-saving, predictable, accountable and effective GBV prevention, risk mitigation and response in emergencies, both natural disaster and conflict-related humanitarian contexts)

- Ending preventable maternal deaths in Asia and the Pacific

- The State of the World’s Midwifery Report - 2021

- Burnet Institute

- Global Standards for Midwifery Regulation

- The Safe Delivery App

- Policy Brief: Quality Midwifery Education needs to address Minimum Global Standards

- Potential impact of midwives in preventing and reducing maternal and neonatal mortality and stillbirths: a Lives Saved Tool modelling study