Background

FGM is recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women. It reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes, and constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against women. It is nearly always carried out on minors and is a violation of the rights of children. The practice also violates a person's rights to health, security and physical integrity, the right to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, and the right to life when the procedure results in death.

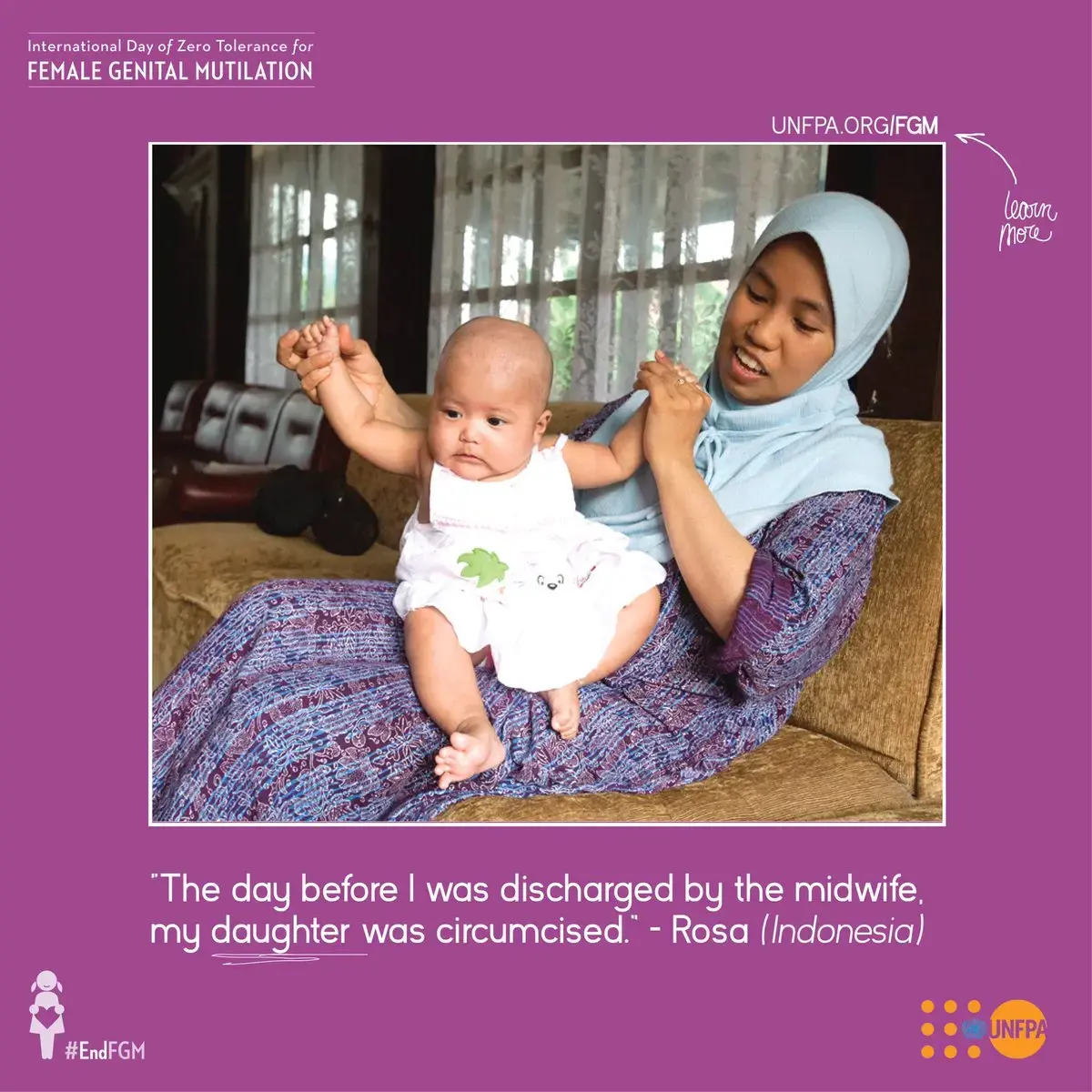

Although primarily concentrated in 29 countries in Africa and the Middle East, FGM is a universal problem and is also practiced in some countries in Asia (notably Indonesia) and Latin America. FGM continues to persist amongst immigrant populations living in Western Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand.

Though the practice has persisted for over a thousand years, programmatic evidence suggests that FGM/C can end in one generation.

UNFPA, jointly with UNICEF, leads the largest global programme to accelerate the abandonment of FGM. The programme currently focuses on 17 African countries and also supports regional and global initiatives, including efforts in Asia.

On 20 December 2012, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution A/RES/67/146 in which it “Calls uponStates, the United Nations system, civil society and all stakeholders to continue to observe 6 February as the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation and to use the day to enhance awareness- raising campaigns and to take concrete actions against female genital mutilations”.

In December 2014, the UN General Assembly adopted without a vote Resolution A/RES/69/150 “Intensifying global efforts for the elimination of female genital mutilations”, callling upon member States to develop, support and implement comprehensive and integrated strategies for the prevention of FGM including training of medical personnel, social workers and community and religious leaders to ensure they provide competent, supportive services and care to women and girls who are at risk of or who have undergone FGM.

The resolution also acknowledges that intensifying efforts for the elimination of FGM is needed, and in this regard, the importance of giving the issue due consideration in the elaboration of the post-2015 development agenda.

Procedures

Female genital mutilation is classified into four major types.

Clitoridectomy: partial or total removal of the clitoris (a small, sensitive and erectile part of the female genitals) and, in very rare cases, only the prepuce (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris).

Excision: partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (the labia are "the lips" that surround the vagina).

Infibulation: narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the inner, or outer, labia, with or without removal of the clitoris.

Other: all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, e.g. pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing the genital area.

No health benefits, only harm

FGM has no health benefits, and it harms girls and women in many ways.

It involves removing and damaging healthy and normal female genital tissue, and interferes with the natural functions of girls' and women's bodies.

Immediate complications can include severe pain, shock, haemorrhage (bleeding), tetanus or sepsis (bacterial infection), urine retention, open sores in the genital region and injury to nearby genital tissue.

Long-term consequences can include: recurrent bladder and urinary tract infections; cysts; infertility; an increased risk of childbirth complications and newborn deaths; the need for later surgeries. For example, the FGM procedure that seals or narrows a vaginal opening (type 3 above) needs to be cut open later to allow for sexual intercourse and childbirth. Sometimes it is stitched again several times, including after childbirth, hence the woman goes through repeated opening and closing procedures, further increasing and repeated both immediate and long-term risks.

Although the practice of FGM cannot be justified by medical reasons, in many countries it is executed more and more often by medical professionals, which constitutes ones of the greatest threats to the abandonment of the practice.

A recent analysis of existing data shows that more than 18% of all girls and women who have been subjected to FGM have had the procedure performed by a health-care provider and in some countries this rate is as high as 74%.

Who is at risk?

Procedures are mostly carried out on young girls sometime between infancy and age 15, and occasionally on adult women. In Africa, more than three million girls have been estimated to be at risk for FGM annually. About 140 million girls and women worldwide are living with the consequences of FGM. In Africa, about 92 million girls age 10 years and above are estimated to have undergone FGM. The practice is most common in the western, eastern, and north-eastern regions of Africa, in some countries in Asia and the Middle East, and among migrants from these areas.

Cultural, religious and social causes

The causes of female genital mutilation include a mix of cultural, religious and social factors within families and communities. Where FGM is a social convention, the social pressure to conform to what others do and have been doing is a strong motivation to perpetuate the practice. FGM is often considered a necessary part of raising a girl properly, and a way to prepare her for adulthood and marriage.

FGM is often motivated by beliefs about what is considered proper sexual behaviour, linking procedures to premarital virginity and marital fidelity. FGM is in many communities believed to reduce a woman's libido and therefore believed to help her resist "illicit" sexual acts.

When a vaginal opening is covered or narrowed (type 3 above), the fear of the pain of opening it, and the fear that this will be found out, is expected to further discourage "illicit" sexual intercourse among women with this type of FGM.

FGM is associated with cultural ideals of femininity and modesty, which include the notion that girls are “clean” and "beautiful" after removal of body parts that are considered "male" or "unclean". Though no religious scripts prescribe the practice, practitioners often believe the practice has religious support.

Religious leaders take varying positions with regard to FGM: some promote it, some consider it irrelevant to religion, and others contribute to its elimination.

Local structures of power and authority, such as community leaders, religious leaders, circumcisers, and even some medical personnel can contribute to upholding the practice.

In most societies, FGM is considered a cultural tradition, which is often used as an argument for its continuation. In some societies, recent adoption of the practice is linked to copying the traditions of neighbouring groups. Sometimes it has started as part of a wider religious or traditional revival movement.

In some societies, FGM is practised by new groups when they move into areas where the local population practice FGM.

What UNFPA is doing

In 2008, UNFPA and UNICEF established the Joint Programme on FGM/C, the largest global programme to accelerate abandonment of FGM and to provide care for its consequences.

This programme works at the community, national, regional and global levels to raise awareness of the harms caused by FGM and to empower communities, women and girls to make the decision to abandon it.

UNFPA helps strengthen health services to prevent FGM and to treat the complications it can cause.

UNFPA also works with civil society organizations that engage in community-led education and dialogue sessions on the health and human rights aspects of the practice. The Fund works with religious and traditional leaders to de-link FGM from religion and to generate support for abandonment. And UNFPA also works with media to foster dialogue about the practice and to change perceptions of girls who remain uncut.

With the support of UNFPA and other UN agencies, several countries have passed legislation banning FGM and developed national policies to achieve its abandonment.

Read more on the UNFPA website: unfpa.org/FGM