Feature: Cash and voucher assistance in Indonesia

Cash covers the ‘last mile’ for HIV care in Indonesia

During the pandemic, UNFPA Indonesia started a cash assistance program that targets women living with HIV and women partnering with people living with HIV. The economic impact of COVID-19 and the unique vulnerabilities of this population group, created new barriers to access health services. The initiative provides a direct cash transfer to help people get to the health centers for life-saving HIV treatment.

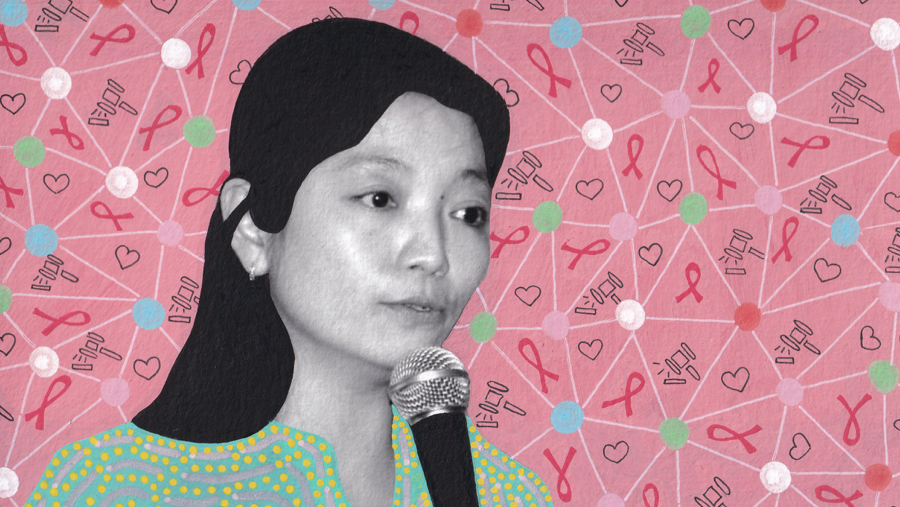

“It is really the last mile of access,” says Oldri Sherli Mukuan. “During the pandemic, health services had limited operating hours and there were so many challenges to access the services.”

Oldri is the HIV Program Analyst with UNFPA Indonesia. She was part of the team that implemented the initiative with organizations led sex workers and people living with HIV. Consultations and research found that people living with HIV struggle to access government and social protection schemes. “There are economic barriers for people living with HIV,” she says. “We provide cash for reimbursement of transport costs for groups we identified as highly vulnerable, like female sex workers living with HIV.”

In Indonesia, 200,000 women aged 15 and over live with HIV.

The project is the debut of the cash and voucher model for the UNFPA Indonesia country office. The initiative delivers support in 73 cities or districts around the country. The goal is to reach marginalized groups with tangible support that will make a difference in their health and give them choices for nutrition. Oldri says vulnerable groups are sometimes unable to access social support systems. “Trans women and young people living with HIV are left behind by government social protection schemes due to the absence of national ID card.”

People living with HIV drop out of treatment for a number of reasons. “Often they do not have money to go to the health centers because most treatments are only available in capital cities and they might live in remote areas where the costs for transport are significant.” The cash support is part of a holistic package for the identified people. It connects them to a network that provides therapy and other sexual and reproductive health services.

Ruth Gloria Katharina Saragi is the HIV National Program Associate who worked on the mechanics of how to distribute cash. She says the question they faced was how to disperse the fund transparently. “Cash transfers work really well because it goes through payment service providers like the e-wallet and to the bank,” she says.

Oldri says one of the advantages is that people can access the cash in remote areas. The result has been a significant increase in people coming to the health center to access services. Gloria says the cash model offers flexibility to do follow up. “We can boost the payment later on,” she says. “We have the data and we can put through payments quickly. It is easy because bank transfers are well-established with the local partner organization.”

The initiative works through community based partners to identify people in the network. Recipients need to have an ID card and a bank account number. The payment system provides greater transparency about who is accessing the cash. “We are happy to see that trans women and young people are accessing the cash,” Gloria says. “Data shows women living with HIV are the biggest group, then pregnant women and young people living with HIV were the third largest group.”

“The mechanism is pretty easy," says Wulan (not her real name), an HIV patient who receives the cash payments as part of the project. "I had to fill out a form and sign it. A month after registration I received the first cash disbursement."

Not long after her husband and her tested positive, Wulan lost her husband due to long untreated HIV. Ever since, she has had to work shifts a day to make ends meet as her two children depend on her. But after she got into an accident at work in 2021, when one of her legs was hit by a forklift, she had to leave her job cooking at a canteen.

For Wulan the payments are a lifeline. "Now I have more money for transportation to pick up the medicine," she says. "I get treatment from the hospital." She makes the 45-minute motorcycle ride the hospital in Gresik, East Java, every month to pick up her medicine. "I am happy because the virus is undetected now."

The project uses the detailed data to produce social protection mapping to introduce a model of funding to other partners. “We are trying to bring that model into the national system,” Oldri says, “We can now think about how we might link this innovation into the Ministry of Social Affairs social protection model.”

Gloria says the primary goal was to provide cash to people to enable them to get to the health center, but the direct connection with people gave them the option to expand with additional funds that can be used for other things like food.

Oldri says most people in the network are dealing with high levels of stress and financial uncertainty. “They lost income during the pandemic. They can save the money to buy food. Instead of receiving in-kind food, it is flexible for them to use.”

Through community consultations, the project found that groups have specific needs and the payments present an option to provide targeted support. “Older people need to have laboratory tests on top of the standard support for people living with HIV,” says Oldri. “Lab tests are expensive and we need a system that can reimburse the costs of tests for older people.”

For people living with HIV, the extra funds help ensure safety and security. “They feel secure even though they have no money because they lost income and are coping with unemployment during a pandemic. But having the cash is really a guarantee for them to access services in crisis situations.”

“They feel secure even though they have no money because they lost income and are coping with unemployment during a pandemic. But having the cash is really a guarantee for them to access services in crisis situations.”

Oldri recalls how she met a woman and her daughter who were both living with HIV. They attended a workshop and shared how the project helped them. “Having a household where multiple family members are living with HIV, the cash helped them as an economic lifeline during the pandemic. The mum contributes money from the grant to be used for her daughter's education by buying books for her to go to school.”

Oldri says the cash was an incentive for people living with HIV who do not have an ID card. “The funds motivated people to get on the system and then finally they have an ID card.”

Through sharing effective ideas with government partners, the criteria the team developed to identify the most at-risk groups is now the basis for local social protection schemes and national protection networks.

Gloria says the use of the platform in the pandemic has demonstrated how cash can be used in a crisis. “When there is a disaster,” she says, “we can change the platform into a model that can be adopted by the government to reach the most vulnerable and we can get people direct support with cash and voucher programs.”

Learn more

Indonesia: “Knowing that I have a say and that I’m in control of my own body, I really only learned those things after becoming a sex worker,” says Liana from Indonesia. Liana is used to shattering expectations; as a middle-class university graduate and former accountant, she does not fit the stereotype of a sex worker. She is the national coordinator of OPSI, a network that supports sex workers with services including health care. READ MORE

Indonesia: Muvitasari works for the PKBI (Indonesia Planned Parenthood Association) DKI Jakarta Chapter, which implements a sex worker outreach programme. PKBI DKI coordinates 16 organizations who deliver programmes for female sex workers across 26 districts in Indonesia, including sex workers with disabilities. READ MORE