By Kelli Rogers, Devex (Story originally published by Devex, here.)

BANGKOK — Thirty years ago, Henriette Jansen wouldn’t have guessed she would become a global authority on measuring violence against women. She began her career as an epidemiologist, first studying intestinal parasites in Colombia and later helping strengthen Zanzibar’s health management information system.

“Early on, I didn't even know what it was called, what I was doing to find the relationship between the laboratory results and the living circumstances of people, but that's how I came into epidemiology,” said Jansen, currently technical adviser for violence against women data and research for the United Nations Population Fund.

She returned to school at the age of 40 to deepen her knowledge of medical demography, excited to head to Indonesia afterward to help develop an international master’s in field epidemiology. It was chance, Jansen said, that diverted her from that path into the shadowy field of violence against women data collection — one she knew little about at the time.

An acquaintance working on the World Health Organization’s multicountry study on women’s health and domestic violence asked her to join them in developing the methodology before beginning her job in Indonesia. Jansen never made that carefully planned move to Yogyakarta, where she had envisioned less travel and more time to become part of the community. Instead, she became transfixed by a young field in need of her data storytelling skill set.

“It was a difficult decision at first because I had my mind set on a very different type of life … and at some point this topic just hooked me and it hasn't left me since,” Jansen told Devex from behind her desk in UNFPA’s offices in downtown Bangkok.

Twenty years after that serendipitous job acceptance for WHO, Jansen’s name is synonymous with the gold standard of sensitive data collection. She has helped governments and women’s groups in 35 countries establish surveys to understand violence against women in their nations — and worked as a consultant or adviser on various health statistics projects in 30 more.

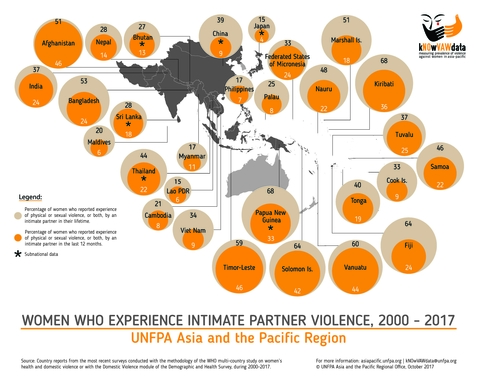

A map highlighting VAW statistics in Asia and the Pacific hangs on her office wall. Worldwide, an estimated 1 in 3 women will experience physical or sexual abuse in her lifetime, and more than half of women interviewed in Timor-Leste and Bangladesh have experienced intimate partner violence, the data visualization reveals. But the numbers don’t discourage 62-year-old Jansen. There isn’t time for that, she says with a disarming smile. The field is still young, and there’s still too little understood — and too much to do.

VAW, then and now

In early July, Jansen is alarmed by a Sri Lankan newspaper headline, which trumpets that a “domestic violence” survey will be conducted in the country later this year. The best practice is to rename a VAW survey for the general public using terms like “women’s health” rather than “violence.” Collecting data about what women often experience behind closed doors requires active discretion in every aspect of the project — and no one knows this better than Jansen.

“She has laid the entire groundwork for in-depth statistical and qualitative research on gender-based violence like no other researcher in the field,” said Mia Rimon, a regional director for The Pacific Community who has worked with Jansen on numerous VAW studies in the region. “She designed the WHO methodology from the very beginning to keep women safe, both the interviewers and the interviewees.”

The last decade has seen a marked increase in donor interest to address the persistence of violence against women and girls. With it, the need for more and better data to inform evidence-based programming to tackle this human rights violation has escalated.

When Jansen started out, she was building on the very few gender-based violence studies conducted in the developing world in the 90s. It was common practice for male enumerators to interview multiple women per household, often in front of men or other potential perpetrators in the house. Under Jansen’s leadership, the exercise of conducting sensitive surveys has changed dramatically. Women enumerators receive extensive training in the art of the interview, surveying only one woman per household in a safe, private space.

The more specific the questions, the more accurate the responses, since women’s definition of general terms like violence or abuse can differ greatly. Rimon calls the design of the questionnaire “masterful.” For Jansen, it’s simply what became clear as a way to respect women and keep them safe, while gleaning information to hopefully be used to change their realities.

Still, as combating violence against women has increasingly become a priority for both governments and donors, mistakes are common. Jansen remembers one country where the survey team presented an official letter to the community leaders about the questionnaire on the day the survey was to begin, detailing exactly what would be asked about domestic violence.

“The men all went running home and told their wives not to collaborate, not to open the door when the interviewer was there,” she recalled.

Another country decided to add general questions about violence to a socioeconomic survey they were already conducting. They used a mix of male and female interviewers and asked general questions of women in front of men. In the end, the country published that just 3 percent of women in the nation had ever experienced violence.

“It was quite surprising — maybe not to the government — but to me, who knew there were several other smaller studies conducted in the country that showed far higher rates. But it’s so easy to go wrong.”

Still other groups decide to move forward with “beautiful” surveys, but without the support of the country’s government — something Jansen sees as a major setback when the ultimate goal of collecting data on violence against women is to use it effectively. It is crucial that government bodies that will interact with the data are involved from the start, understand the methodology, and fully trust the process.

“In the beginning, it was really just ‘we need to collect this data.’ Now it's, ‘we need to make sure that it's being done properly and safely and participatory and in a way that's really being used,’” she said, citing Vietnam’s revision of their domestic violence law following the country’s first eye-opening survey in 2009 as a positive example.

Far more than the numbers, it’s the translation of the data into meaningful stories, interventions, recommendations, and policies that lights Jansen up.

A legacy

Jansen is proud of her work, but she cautions against being too optimistic about where the field is now versus when she started.

“Is [violence against women] still so much of a problem? That's a difficult thing to say because we still have very little evidence. It's only so recent that we know how to measure it and it's too short to really be able to see ... the big picture, if things are changing.”

Jansen has made it her personal mission to fill in the gaps and collect data in the many countries where it’s missing, or where there is still none at all. It’s the variation in data between countries and regions that shows that violence is not inevitable, she said, and helps point to the crucial areas to address it.

Accustomed to extra layers of scrutiny by those who don’t trust her work or feel threatened by VAW findings, Jansen is known around the world for solid data analysis, expertise in tabs and tables, and excellence in planning interventions based on the numbers. But her personable, approachable nature and an abundance of compassion carry equal weight in the work she describes as transformative.

“One of the most rewarding parts is to be involved in interview training, to work with a group of women who are usually quite carefully selected or interested in the topic, and to see them transform and see them change into women who reflect on their own lives, who become better people,” she said. She paused thoughtfully before launching into several stories of women she’s worked with who stopped beating their children after learning that kids who experience violence at a young age are more likely to become perpetrators or victims later in life.

The key component of getting good data, she said, is having the right interviewers with the right skills, who “know how to give the gift of a listening ear and open heart to get a gift in return. And that is often a story that a woman will never tell to anybody else.”

In June, women from 10 different countries gathered in Bangkok for two weeks of interview training. Through UNFPA’s kNOwVAWdata project, they learn technical skills as well as how to develop the rapport with their interview subject that comes so naturally to Jansen.

Building technical capacity to collect data is the primary objective, but there’s another element as well, Jansen explained: “We find that the women who are trained to conduct these surveys often see their own personal stories mirrored by the narratives of the women they’re interviewing. This can be an incredibly emotional, transformative experience for the interviewer, a catharsis that helps lighten her own burden of having experienced violence in her own life.”

The formation of a professional pool of regional experts who participate in the kNOwVAWdata course will ideally help to strengthen the availability and quality of data to inform policy and help end VAW, she explained. But for a woman who embarked on the journey to better understand and end VAW more than 20 years ago, it’s also a crucial step in passing the torch as she approaches retirement.

“The real work so far has depended on a very few handful of people,” she said. “And most of us are retiring.”

Once an avid scuba diver and passionate photographer, Netherlands-born Jansen will have to spend some time re-exploring her hobbies, she joked. The past four years especially have been nothing but work; she hasn’t danced the Argentine tango in forever, she says wistfully.

Instead, her work has led to the “complete turning on [the] head of how GBV is viewed in the Pacific and in many Asian countries,” Jansen’s colleague Rimon told Devex. “She has been the driving force in ensuring that the tools for data collection are sound, accurate, have consistency checks, are logical and lead to robust data sets.”

As Jansen’s confidence grows in the women she’s trained and the research institutions that have signed on to move her life’s work forward, it looks like there might be more time for dancing or underwater exploration in her future. She’s still learning Thai, hoping to add it to the seven languages she already speaks.

But when asked what her plans are for her retirement, Jansen just laughs. It was chance that led her to the most rewarding work of her life. She isn’t one to make plans.

About the author

Kelli Rogers is a global development reporter for Devex. Based in Bangkok, she covers disaster and crisis response, innovation, women’s rights, and development trends throughout Asia. Prior to her current post, she covered leadership, careers, and the USAID implementer community from Washington, D.C. Previously, she reported on social and environmental issues from Nairobi, Kenya. Kelli holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Missouri, and has since reported from more than 20 countries.