By Lily Kuo / The Guardian

A year ago, Saranzaya Chambuu received a distressed phone call from her sister Naranzaya. Their roommate had brought a male friend home the night before. When she left for work, he stayed. Hours later, Naranzaya called her elder sister. “She was crying and asking: ‘Who was that man? He raped me and then he left.’”

That man, they would soon learn, was a ruling party MP, Gantulga Dorjdugar, who is now under investigation. He says he has been wrongly accused and the two “mutually consented” to having sex.

It is one of the most high-profile political scandals in Mongolia in years, and highlights both the progress and the challenges in a nascent but growing women’s rights movement. Saranzaya, 32, is one of a small but increasingly bold group of women calling on their country to tackle pervasive sexual violence.

For some, this is the beginning of Mongolia’s #MeToo movement, though weak laws and a culture of victim-blaming mean it has a long way to go.

“Some people ask why don’t we stop and why are we fighting for this,” Saranzaya said. “We want to make a path for other women. If this can win in court and they can bring justice to victims, we can prove the system is just and that will help other victims.”

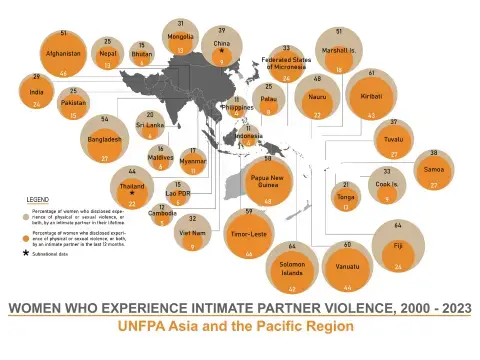

According to Mongolia’s first nation-wide survey on gender-based violence, released on Thursday by the national statistics office and the UN Population Fund (UNFPA), 31% of women say they have been subjected to sexual or physical violence by their partner.

One in seven women (14%) say they have been subjected to sexual violence by someone who was not their partner – a figure twice as high as the estimated world average and higher than almost anywhere else in Asia, according to Henriette Jansen, a UNFPA adviser.

“In Mongolia there is huge variation in proportions of women experiencing non-partner sexual violence throughout the country. It is everywhere and sexual abuse against women is quite alarming compared with the rest of the region,” said Jansen.

One in seven women (14%) say they have been subjected to sexual violence by someone who was not their partner – a figure twice as high as the estimated world average and higher than almost anywhere else in Asia, according to Henriette Jansen, a UNFPA adviser.

“In Mongolia there is huge variation in proportions of women experiencing non-partner sexual violence throughout the country. It is everywhere and sexual abuse against women is quite alarming compared with the rest of the region,” said Jansen.

But a backlash is building. In March a group of women knitted hundreds of red pussyhats and wore them to a protest against violence in the capital on International Women’s Day. In May a women’s group held a performance of the Vagina Monologues, translated into Mongolian.

In 2016, after years of lobbying by activists and female lawmakers, the country made domestic violence a crime for the first time. Now a consortium of NGOs is pushing for sexual harassment in the workplace to be included in the country’s labour laws. Sexual assault or abuse below the level of rape is handled by the country’s human rights commission, which can only make recommendations.

Justice delayed

While awareness is increasing, justice is still rare. Naranzaya’s case stalled at first when two doctors who first examined her took a leave of absence and then were replaced. The case was reopened in August after Naranzaya’s family provided items – underwear and a duvet – found to have traces of Gantulga’s semen. Gantulga, whose lawyer did not respond to requests for comment, has repeated his client’s assertion of innocence.

The national survey found that only 10% of women who said they had experienced “severe sexual violence”, including rape, from someone who was not their partner, said they reported their case to the police. A separate survey of 300 rape victims by the Gender Equality Centre found that about 65% of reported assaults went to trial. Just 9.5% of victims polled said they had received compensation. Police data shows victims get on average 804,854 tugrik – about £250.

Women who speak out are often blamed. Late last year Bolor Zaankhuu, 33, published her own #MeToo account. Fifteen years ago, while taking an elevator up to her fourth-floor apartment, a man grabbed her from behind and groped her, she wrote in a blog. She struggled until the elevator doors opened and she ran out and down the stairs to the ground floor. When she went to the police with her father, she recalled, she was reprimanded for wearing a tank top. It was the middle of summer.

“Immediately I was blamed,” she said. Bolor later identified her attacker, who spent one night at the police station before being let go. Now, she said, she waits to take elevators until no men are around and she doesn’t allow her 10-year-old daughter to go anywhere alone.

A woman who lives and works in Ulaanbaatar said that on one occasion four years ago she woke up in a hotel to find a man raping her. Later when she filed a police report alleging she had been drugged and assaulted, the investigator said she was not likely to get compensation and encouraged her to drop the case. Eventually she did.

“I don’t feel bad about it any more. At least, I want to shake that mindset. Women feel guilty. Because they got drunk or because they went to that party, they blame themselves … that if I hadn’t been wearing this or that, then this wouldn’t have happened,” she told the Guardian, asking that her name not be published.

Women have contacted Saranzaya to say they too have been victims of sexual assault, but no one has joined her campaign. The sisters have been called prostitutes and liars. Others say Saranzaya is using her sister to try to extort money from the MP. Even women’s rights groups have stayed away after critics accused Saranzaya of being politically motivated.

Hospital shelter

Researchers and advocates are worried not just about the extent of sexual violence in Mongolia but the severity of it. The survey found 72% of women who said they had been injured by their partners reported “severe” harm such as broken bones, cuts to the head and in some cases miscarriages. Researchers found forms of abuse particular to Mongolia: hundreds of women reported being chased by their partners in cars, on motorcycles or horses, or being lashed with whips.

The number of people reporting abuse is growing, a statistic that could mean more people are willing to do so, or abuse is on the rise, or some combination of the two.

At the One Stop Service Centre, a small office and room with bunkbeds at Ulaanbaatar’s main trauma hospital, abused women can shelter with their children for up to 72 hours and seek medical help, therapy and legal advice.

Deedentsetseg Chuluunbayar, a social worker at the centre, said that in 2008, the first year it was open, it received around 300 women. Last year the number was 960, despite the centre closing for a month, and now it gets at least eight women a day. On payday and public holidays, more women come to the hospital with injuries. On 18 March, Soldier’s Day in Mongolia, 15 women came to the centre.

Deedentsetseg said Mongolia’s new domestic violence law could lead to fewer women reporting abusive partners. In the past, women reported their husbands to the police to scare them, and then they would drop the case. Under the new law, domestic violence cases have to go forward to trial.

“It’s really a difficult situation because most of the women who come here don’t want to disrupt the family and are dependent on their husbands,” Deedentsetseg said.

‘Reverse gender gap’

It is unclear why sexual violence is apparently so prevalent in Mongolia, a middle-income country that prides itself on its peaceful transition from a former Soviet satellite to a democracy in 1990.

Some blame a macho culture, while others point to a “reverse gender gap”. For years after the transition, families invested more of their resources in sending their daughters to school and kept their sons home to herd.

Mongolian women now outpace men in education, health and work. Men have higher rates of unemployment and alcoholism, and their average lifespan is 10 years shorter than that of women.

“Men’s reputation has fallen. These things can be a reason why more men are angry with women, which leads to violence,” said Boldbaatar Tumur, head of the Men’s Association in Gobisumber province, which works on raising awareness of men’s issues.

Others say Mongolia’s close-knit rural communities encourage a culture of silence. “Very few people can say ‘me too’,” said Oyungerel Tsedevdamba, a former MP who pushed for the law criminalising domestic violence. “In the countryside there is no anonymity, and because of that no one wants to speak out.”

Gerelee Odonchimed, vice-director for education and advocacy at Women for Change, a women’s empowerment group, said Mongolia’s women rights movement needed more patience. “It can be slow but, yes, time is up,” she said. “We aren’t talking about changing the colours of the walls. We are talking about changing people’s minds.”

Saranzaya and Naranzaya are also taking things slowly. They have moved into a new apartment and Naranzaya, 26, is back at school, studying to become a teacher. “She’s starting to feel OK again,” Saranzaya said of her sister.

This week Gantulga, the accused MP, resigned from parliament. Saranzaya has noticed that when the case is in the news again, her sister slips back into a depression. She has wondered whether they ought to drop the case and move on with their lives. “I said if it’s too difficult we can stop, but she says no, we will fight together.”

Additional reporting by Munkhchimeg Davaasharav